What do Britpop and Tony Blair have in common?

Besides being relics of the 90s which arguably ought to be forgotten but fascinate me nonetheless

I recently read The Last Party: Britpop, Blair, and the Demise of English Rock by John Harris. For about five years I have been trying to combine my separate interests in English rock music and UK politics, specifically New Labour, into something worthy of serious academic study. I have yet to really succeed, so this book sounded like required reading for me.

Sadly, it was disappointing on the Tony Blair front, but I did learn a lot about the major players within Britpop, and it gave me things to ruminate on re: my own hypothetical music/politics project. What follows is an externalization of some of that rumination. Skip if you so choose.

Harris had a nice musical definition of Britpop, but I had to return the book to the library and forgot to write it down, so I can’t quote it. At any rate, I’m more interested in the ideological dimension. Around 1993, there emerged a cluster of bands (primarily Suede and Blur) focused on producing authentically British rock music, in opposition to the Nirvana-driven fad for American grunge.

After Oasis joined the scene, the goal shifted from writing songs in the rich tradition of intellectual British indie rock, to getting out of the cloistered, ostracized indie world and making it really big in mainstream pop. Blur and Oasis were especially open about aiming for a mass audience of all ages rather than a countercultural youth following.

There’s an obvious parallel here with Tony Blair’s efforts to win over middle Britain by stripping away the Labour Party’s past association with hard left intellectualism. After modernizing the party, in 1997 he campaigned on a platform that included rebranding the whole nation for the 21st century.

It’s no surprise, then, that Blair’s Labour Party allied itself with Britpop. Appearing in the company of some of the most popular musicians in the country built up Blair’s image as a hip, with-it politician and furthered his goal of crafting a new national identity that everyday Britons could take pride in. While this alliance had little influence on government policy, what minimal policy-flavored discussion there was focused not so much on Britain’s wealth of creative genius, but on the entrepreneurial and economic potential of the music industry.

This focus on music as economic market indicates Blair’s broader commitment to neoliberalism, which was the starting point for a paper I wrote in college. I investigated whether New Labour’s claims of modernization and innovation had any truth, or whether Blairism was just Thatcherism repackaged. The same sort of question could be posed of Britpop: was it breaking any new musical ground, or just rehashing the three decades of pop and rock music that preceded it?

In this playlist, I trace some of those various rehashed influences. In terms of my own broader academic interests, I’m interested in how all of these musical eras contribute to identity formation on a subcultural and national level. I’m also interested in what’s getting left out, at least in the established narrative put forth by the likes of John Harris. All of the bands featured here are white. It’s kind of crazy to depict 90s groups looking to their forefathers as the torch-bearers of some uniquely British art form, when all those bands were building on American rock ‘n’ roll and/or Jamaican reggae, among other non-British and nonwhite genres.

Those influences are certainly deserving of their own playlist, but this one focuses on the British bands cited as immediate influences on Britpop, plus a smattering of Britpop itself. The following songs were selected for their commentary on British identity, their overall significance, or, with bands I’m less familiar with, because John Harris discussed them in his book.

One major Britpop influence I didn’t include is British music hall. This was particularly taken up by Blur, as well as many of the bands featured here that came before them. Someday I’ll write more about that.

“Anyway, Anyhow, Anywhere” by The Who (single, 1965)

The most prominent of the original Mods, a subculture that has reemerged again and again in British music.

“Making Time” by The Creation (single, 1966)

“Waterloo Sunset” by The Kinks (Something Else by the Kinks, 1967)

Damon Albarn of Blur cited this as an example of the kind of song, romanticizing the mundanity of British life, that could not be produced by an American band and that he wanted to bring back. On their next two albums, however, the Kinks’ representation of British identity was decidedly satirical, so I find the earnest appreciation of their Britishness kind of funny.

“I Am The Walrus” by The Beatles (Magical Mystery Tour, 1967)

Obviously the Beatles have influenced everyone who came after them, more or less. I chose this song because Oasis used it as a closer at their concerts, but if you listen to any mid-to-late-career Beatles song and then any Oasis song you’ll hear the musical debt.

“Lazy Sunday” by Small Faces (single, 1968)

I’m going to be honest, I find this song unlistenable, but the Gallagher brothers often cited Small Faces as a major touchstone, and the emphasized working class accent obviously showed up again.

“Jumpin’ Jack Flash” by The Rolling Stones (single, 1968)

“Soul Love” by David Bowie (The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, 1972)

Like the Beatles, Bowie’s influence is so vast that it’s kind of silly to try to sum it up. Even if the Small Faces did it first, he is more often cited as popularizing the affected, emphasized accent.

“Virginia Plain” by Roxy Music (Roxy Music, 1972)

“God Save the Queen” by The Sex Pistols (Never Mind The Bollocks, Here’s The Sex Pistols, 1977)

Quite literally a cultural reset. Harris points out that, beyond the Sex Pistols’ generally upheaving impact on the British cultural scene, John Lydon’s specific way of enunciating certain sounds was later picked up by Liam Gallagher.

“London’s Burning” by The Clash (The Clash, 1977)

Harris actually doesn’t talk about the Clash much, but their first album had a lot of overlap with the Sex Pistols’ body of work. After that, they took a more global perspective. In my opinion that produced a much more interesting commentary on English life, but I’m trying to represent direct influences, not my own taste.

“Lowdown” by Wire (Pink Flag, 1977)

Elastica were particularly inspired by Wire (to the point of borderline plagiarism in at least one case).

“That’s Entertainment” by The Jam (Sound Affects, 1980)

As mentioned above, the original 60s Mods have been hugely influential on British culture, but this was particularly true during the Mod Revival of the late 70s. Of the surprisingly high (at least to me) number of bands that emerged in this moment, The Jam are the only ones to live on in general memory.

“Our House” by Madness (The Rise & Fall, 1982)

“Still Ill” by The Smiths (The Smiths, 1984)

Pretty much every rock musician in the 90s had grown up listening to the Smiths, and Blur and Suede at least partially got into music with the goal of imitating them. (Bernard Butler of Suede learned Johnny Marr’s guitar parts by listening to concert bootlegs.)

“Some Candy Talking” by The Jesus and Mary Chain (Some Candy Talking EP, 1986)

The Jesus and Mary Chain toured with Blur in 1992 and later shared a label (Creation) with Oasis.

“Wrote for Luck” by Happy Mondays (Bummed, 1988)

I’m including this and the next song only for completion’s sake because I know next to nothing about both bands. However, because I was listening to these albums while reading Harris’s book, Spotify now keeps making me daylists with titles like “madchester britpop wednesday morning.”

“I Am the Resurrection” by The Stone Roses (The Stone Roses, 1989)

“Only Shallow” by my bloody valentine (Loveless, 1991)

Another Creation Records group.

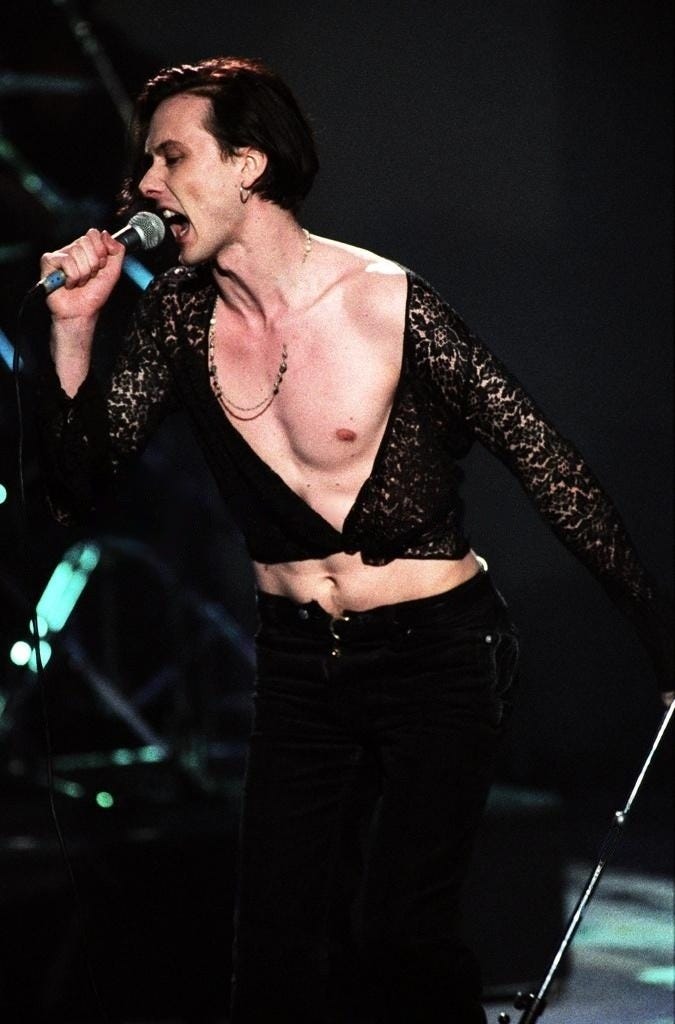

“Animal Nitrate” by Suede (Suede, 1993)

Suede led the first wave of Britpop before it was known as Britpop, when it was still just the latest chapter of British indie rock. Brett Anderson earned comparisons to David Bowie and Morrissey through his androgynous stage persona and sexually ambiguous lyrics.

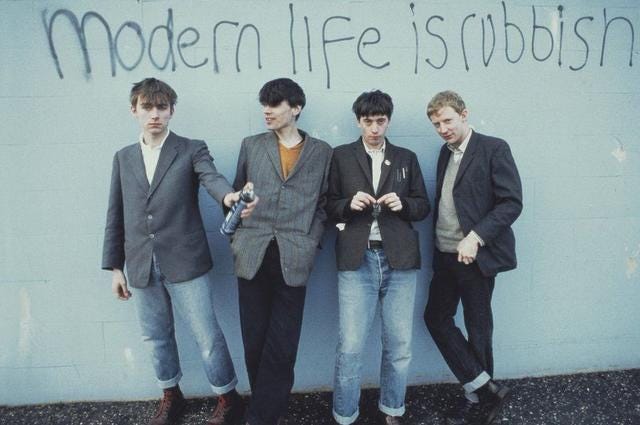

“For Tomorrow” by Blur (Modern Life Is Rubbish, 1993)

While Suede were incidentally expressing something fundamentally English through their lyrics, Blur found success by making the depiction of quintessential English life, expressed through Albarn’s accented vocals and character-driven lyrics, their whole brand. Albarn openly posed this as a reaction against American grunge.

“Stutter” by Elastica (single, 1993)

Elastica was started by two former Suede members, including Justine Frischmann, who fell out with Brett Anderson after she dumped him for Damon Albarn. Artistic tensions and heroin addiction prevented the band from releasing more than one proper album, but this was the first in a string of singles that helped define the Britpop sound.

“Columbia” by Oasis (Definitely Maybe, 1994)

When Oasis came on the scene, they were proudly working class and anti-intellectual, espousing bands of the past who were made up of proper blokes playing basic rock music for everyday people. (Included in this category were the Beatles, which raises some questions about Liam Gallagher’s listening comprehension.)

“Girls & Boys” by Blur (Parklife, 1994)

This year, and this album in particular, marks the point where Britpop ceased having much to do with the indie scene and became about topping the charts and attracting the biggest audience possible. The term “Britpop,” coined the year before, came into common parlance. The following year, record sales became even more central during the “Battle of Britpop” — a media frenzy over who would get a number one album, Blur or Oasis. This was a wild departure from the previous norms of the indie scene, where bands hardly ever received coverage outside the music press and could attain success without ever coming close to topping the charts.

“Never Here” by Elastica (Elastica, 1995)

“Don’t Look Back In Anger” by Oasis ((What’s The Story) Morning Glory?, 1995)

I truly do not care for Oasis, but I must admit that this remains a banger. It’s such a Beatles rip-off, though.

“Common People” by Pulp (Different Class, 1995)

John Harris lost my respect by barely devoting any space in his book to Pulp, who are imho the best and most interesting Britpop band, but he does point out that Jarvis Cocker was the only songwriter in his cohort expressing actual anger about the conditions of the working class lifestyle being blithely glamorized by everyone else.

“Death of a Party” by Blur (Blur, 1997)

I’m very Blur-neutral but I think this song rules, and it’s an apt note to end on, given that Britpop fell apart after only a few years, thanks to the classic combination of changing public taste, industry bust following a boom, and drug-fueled burnout. By this point the band members themselves had become tired of being seen as a pop group. This album was an attempt to reclaim their indie rock roots.

“Cocaine Socialism” by Pulp (b-side, 1998)

All that stuff about Tony Blair at the beginning was just a set-up so I could finish with this song. A fairly true-to-life satire about Blair courting musicians for PR support, and a kind of devastating indictment of New Labour’s lack of substance and the flimsy morals of the musicians (primarily Damon Albarn and Noel Gallagher) who supported the party.

If you want a more thorough but less organized Britpop sampler, I also kept a running playlist of songs mentioned in The Last Party while I was reading.

I suppose I should end with some attempt to answer the question I posed at the top, about whether Britpop was a legitimately innovative musical movement or a historical rehash. But I’m afraid that I am wedded to nuance, so my honest answer is the same conclusion I came to in my Tony Blair paper: it’s a little of both!

I think the bigger issue with Britpop was not its lack of originality, but its commercialism. It would be an overstatement to say that Blur, Oasis, and the others were solely responsible for destroying Britain’s unique indie rock ecosystem, because there were plenty of other contributing factors and indie music reemerged later in various forms. But I have too deep an anti-capitalist, counter-culture streak not to find Britpop’s obsession with mass appeal a little revolting.

Except for Pulp. Long live Jarvis and please don’t ask me how much I’m spending to see them twice this fall.